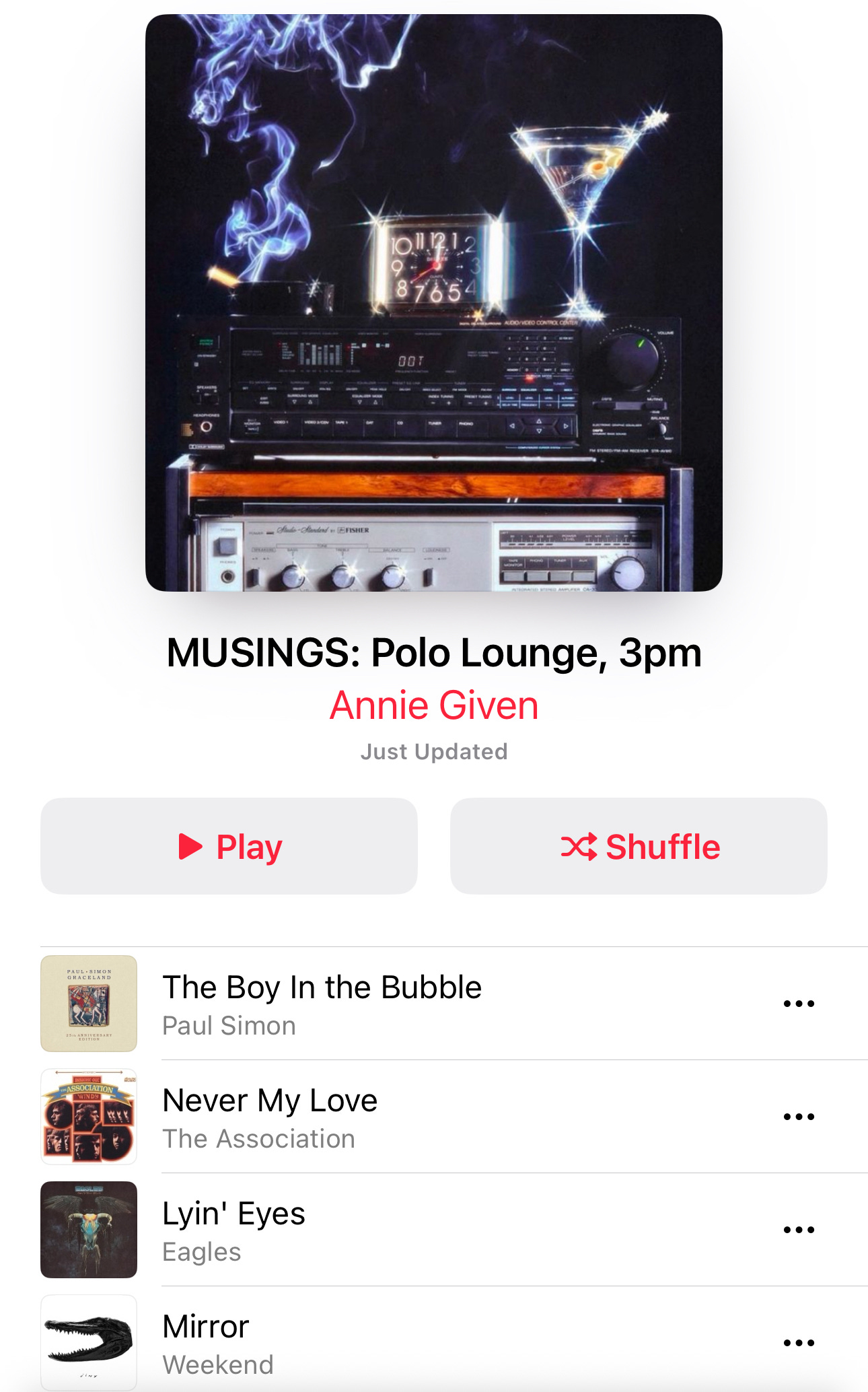

I met him at the Polo Lounge, which, in hindsight, already sounds like the beginning of something unwise. Looking back, I don’t remember why I was there—visiting a friend’s friend’s boyfriend who was in town from Dallas, perhaps. It was late afternoon, the sun filtering in through linen curtains, the kind of place where the martinis taste like polished glass and everyone looks a little too tan, a little too still. I was twenty—maybe twenty-one. That age when you mistake mystery for sophistication, when you think older men must know something you don’t.

He sat across from me in a pressed linen shirt, a hideous blue-and-gold Rolex Submariner visible just beneath the cuff—a flex he’d long since stopped pretending to hide. He was handsome in a dated, finance-adjacent kind of way: square jaw, soft gut, the kind of man who had peaked in 1997 and now wore his decline with a mix of denial and bravado. He told me his son went to Harvard-Westlake, as though it were something I should find impressive. I only nodded, did the math—he was around my father’s age.

We met for lunch from time to time. That was our thing. Always at the Polo Lounge or somewhere equally lacquered and hushed. Places where everyone knows not to look too closely. He’d order something archaic—crab Louie or steak Diane—and drink during the day like it was still 1989. Sometimes I think he didn’t know what to do with me. I certainly wasn’t sleeping with him. I wasn’t trying to marry him. I was just… there. Detached. Maybe a little too observant.

He worked in finance—though that could mean anything in Los Angeles. Real estate, private equity, asset management. The details were vague by design, and I never pressed. The answers bored me anyway. What intrigued me wasn’t what he did but that he kept showing up. Not always physically—though sometimes that too—but digitally, subtly, almost hauntingly. A text every few weeks. A cryptic reply to an Instagram story. And the money. Venmo payments that arrived without warning: $300. $500. Once, $1,000. Each with some innocuous caption—“Lunch on me,” or just a single emoji. A martini glass. A camera. A ghost.

I didn’t understand. Did he think he had to pay me for my time? I sent the first one back. He protested—No, no, on me. I insist. I worried, for a while, that he thought this was transactional. That I was something to be rented, not known. And still, the gifts continued. I stopped returning them eventually, not out of agreement, but exhaustion. It was easier than arguing with a man determined to turn generosity into control.

I never really understood it. We were never lovers. No hotel room, no lingering kiss goodbye. Just this strange emotional tether he kept tugging on, like a child with a balloon string, unsure if he wanted to let it fly away or pull it closer.

He had a girlfriend. Of course, he did. Ten years, he said. “Wonderful,” he called her, like a line he’d rehearsed. Everyone loved her. Patient. Elegant. The kind of woman who knew how to survive men like him. But one afternoon, over lunch, he changed the script.

We were sitting outside, under one of those ridiculous green umbrellas. The waiter had just set down our drinks. I remember the exact moment: the olive in his martini casting a long, greenish shadow on the white tablecloth.

He leaned back, almost casually, and said, “You know, she’s not who people think she is.”

I raised an eyebrow, half-interested. “Oh?”

“She used to be hot. Like, really hot. Model hot,” he said, as though this were a casual observation. “Now she’s just… trying. You know how women get when they’re past the point. The desperation. The surgery. The clinging.”

I didn’t say anything. I stirred my iced tea, waiting for the moment to pass. But he kept going.

“She gets jealous if I even look at someone younger. The insecurity is exhausting. Honestly, sometimes I stay out just so I don’t have to go home to it. And the sex? Forget it. She thinks just being there is enough. I mean, come on.”

He laughed then. A dry, barking laugh, like tires skidding on gravel. I remember staring at him, trying to rearrange my face into something neutral, something that didn’t reveal how suddenly sick I felt.

That was the moment. The one that split the image from the man.

Up until then, I had constructed a version of him that was pitiful but charming, flawed but forgivable. A man out of time. A sad Gatsby in mirrored aviators. But what he said—how casually he said it—peeled something back. Something mean. Something rotted.

And yet.

He told me, once, in a moment that felt too soft for him—after the waiter had cleared the oysters and before the second round of drinks—that he liked photography. Said it like a confession. “Just black-and-white stuff. Old cameras. Nothing serious.” He said this with the same tone he might have used to admit crying at movies or listening to Joni Mitchell alone in his car. It was the only thing he ever told me that felt like it belonged to him, not to the version of himself he wore like a custom Brioni jacket. For a second, I saw someone else there. Someone small and curious and vaguely sweet, buried under layers of performance and self-preservation.

That moment didn’t last long. It slipped away, as they always do with men like him. He wasn’t interested in being known. He wasn’t interested in anything real. He was only interested in the theater of it all—the performance of life.

I looked at him and saw the whole act for what it was: theater. He wasn’t lost. He wasn’t wistful. He was cruel. A man so terrified of fading into irrelevance that he’d slash at anyone who reminded him that time was moving on without him.

He flirted constantly. Waitresses, assistants, baristas. His eyes scanning for targets like a heat-seeking missile. But there was nothing sexy about it. No real thrill. Just compulsion. He didn’t cheat because he needed to. He cheated because he didn’t know how not to. It was identity for him. Religion. Proof of life.

I certainly didn’t love him. I didn’t even really like him. But I watched him. Closely. With the kind of fascination reserved for things you don’t understand but know you should avoid.

He was trying so hard to be large, commanding, immortal. But underneath it all, he was small. Shy. Embarrassed. A man who knew, somewhere deep inside, that the game was over but still insisted on moving the pieces.

And me—I was just another pawn he nudged across the board, not realizing I wasn’t playing.

Just watching. Remembering.

In the end, he wasn’t an artist. He wasn’t even interesting. Just another man with too much money and too little imagination, mistaking attention for affection, mistaking silence for consent.

I was never his muse. I was just a mirror.

And he couldn’t stand the reflection.

a dime a dozen of these boozers at the BH Polo Lounge but it's still fun. :D

"Always at the Polo Lounge or somewhere equally lacquered and hushed. Places where everyone knows not to look too closely."